A long time ago, longer than I would care to admit, I was asked to develop a Christmas themed tour for a well-known Boston Tour organization. The tourism industry goes into a bearlike hibernation as soon as winter sets in, and my boss at the time wanted a reason to keep people interested in the brand at least through the winter. The American Revolution being Boston’s calling card, I think the hope was that I would dig up a letter containing Christmas wishes from the romantic correspondence of John and Abigail Adams or a story of Paul Revere crafting presents some number of the 16 children who passed through his house.

I had to break it to them that tricorns under the mistletoe wasn’t a thing (and besides, they are called cocked hats). The Puritans had officially banned the celebration of Christmas in 1659, and though the ban was lifted in 1683, observance continued to be frowned upon. In 1712 Cotton Mather, author of witchcraft pamphlets that fueled the Salem Hysteria, turned his poison pen to Christmas, the holiday he called the “Pagan Saturnalia”:

The Feast of Christ’s Nativity is spent in Reveling, Dicing, Carding, Masking, and in all Licentious Liberty … by Mad Mirth, by long Eating, by hard Drinking, by lewd Gaming, by rude Reveling …

I had the sad duty of informing my boss that this was still the state of affairs come the Revolutionary era and that with the possible exception of a hessian mercenary, perhaps, no one was celebrating with a Christmas tree in North America. The good news, though, was that there was great Christmas History in Boston, but in the 19th century.

By then, Italian and Irish immigrants were arriving in large numbers and bringing with them all manner of “popery”, including the celebration of Christmas. Things were helped along with images that arrived from England of Victoria and Albert decorating a Christmas tree. But if there was a moment that Christmas tradition in Boston truly solidified, it was December 24th of 1867- and the best news was that a physical remnant of that moment was and is on display on the mezzanine level of Boston’s Parker House Hotel. Take a left out of the elevator and you will stand before a massive mirror, accompanied by a plaque that reads:

Mirror from the rooms at the Parker House occupied by Charles Dickens 1867 & 1868 authenticated by the Boston branch of the Dickens Fellowship.

Look closely and see reflections of Dickens as he practiced a ‘Christmas Carol.’

Dickens Mirror, Omni Parker House

There is no Christmas story so beloved as Dickens “Christmas Carol” and the fact that he had done a live reading to a rapturous Boston audience next door to the Parker House at the Tremont Temple proved excellent fodder for a holiday history tour. The Parker House hotel likewise proved an excellent partner and the tour- which comes with a complimentary Boston Cream Pie at the hotel- continues to this day.

Fast forward a couple of years later, I was visiting my grandmother’s old farm in the Adirondacks, looking at an old bookcase I had lazily stared at hundreds of times from childhood on, when suddenly a title jumped off of the spine of one of the books and smacked me in the face: Dickens Days in Boston. I leaped of the couch and pulled out a book that was almost 100 years old.

It turned out to be a day by day, nearly minute by minute account of Dicken’s visit to Boston in 1867 I’d like to share with you some of the stories I read there about his performance of ‘A Christmas Carol’ and what it meant to the most famous Bostonians of that time, in what was arguably the most memorable Christmas season in Boston history.

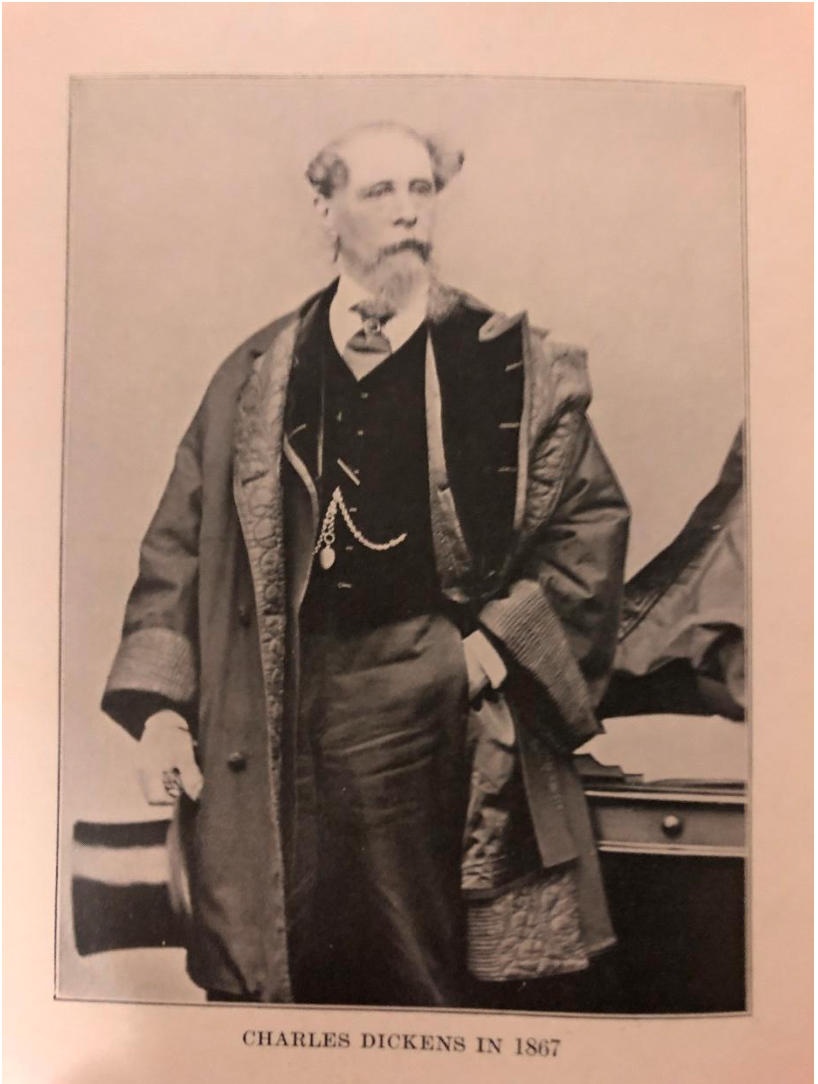

It was to be Dicken’s second visit to Boston after an absence of 25 years, and in that time his fame had grown considerably thanks in no small part to the publishing of “A Christmas Carol” in 1843 shortly after his first visit. Anticipation of his arrival was high and connections he had made in 1842 were eager to renew their friendship. Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s diary entry for Monday November 18th, 1867 read as follows:

After the snow of last night there was a bleak west wind. I saw great crowds waiting, in line, outside of Ticknor and Fields at Tremont Street, to buy tickets for Dickens’s readings. Dickens himself being expected tomorrow, as the steamer was at Halifax on this day.

That ship, the Cuba, arrived on November 19th as Longfellow predicted. By then the tickets for all four scheduled readings, which were to begin on December 2nd, were completely sold out.

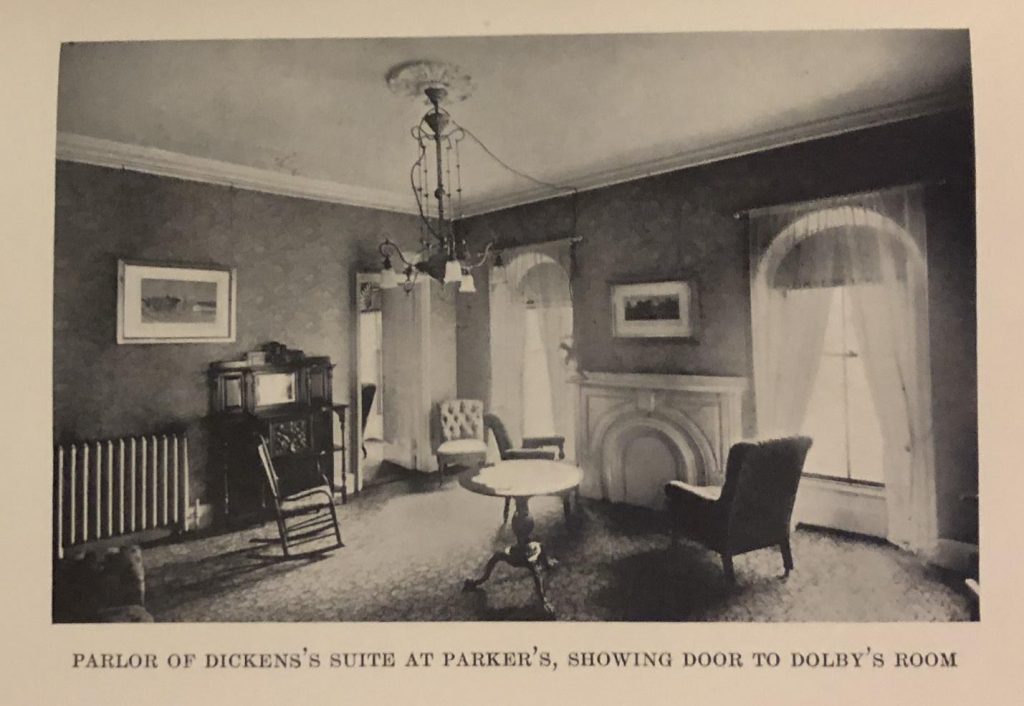

Annie Adams Fields, wife of Dicken’s publisher and close friend James T Fields, personally festooned Dickens’ suite at the Parker House with flowers and even stocked a bookcase with the best of Ticknor and Fields publications. James, Dicken’s closest friend in Boston, couldn’t wait for the Cuba to dock and rode out onto the harbor in a customs house boat to meet the Cuba before escorting Dickens to the Parker House.

Longfellow also wasted little time in rekindling his acquaintance, calling on him at the Parker House on the 20th. After a quarter century apart Longfellow remarked that Dickens looked “somewhat older, but as elastic and quick in his movements as ever”.

As he dined with old friends and took daily 8-10 mile walks (!) with James T Fields, Dickens renewed his preparations for the readings that were causing such an anticipatory sensation:

There was a great mirror framed in decorated black walnut on one side of the parlor, and before this mirror he went over and over the lines and business of his wonderful impersonations.

It was his way to commit his selections to memory and they wee really monologues, more acted than read, and he did not always follow the printed test, but added material he thought necessary to heighten the effect.

Longfellow House circa 1920

Dickens would have Thanksgiving dinner at what is today referred to as the Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters. It was a muted affair, however; for Dickens, a well known teller and collector of ghost stories, could not help but focus upon the tragic death of Fanny Longfellow who he had met there in 1842. Dickens wrote of it in multiple letters, including one to his daughter:

[Longfellow] is now white haired and white bearded, but remarkably handsome. He still lives in his old house where his beautiful wife was burnt to death. I dined with him the other day and could not get the terrific scene out of my imagination. She was in a blaze in an instant, rushed into his arms with a wild cry, and never spoke afterwards.

On November 30th, the Saturday following Thanksgiving, Dickens was received at the Parker House at the monthly meeting of the Saturday Club, a monthly affair where America’s greatest authors were feted by Harvey Parker and his French chef Sanizan.; frequently these affairs extended past seven courses and flowed with sherry, claret, and Sauterne. The presence of Dickens led to an even grander party than usual; Dickens stayed for six hours and Annie Fields noted that James had “never stayed so late before. The dinner begins at half past 2 and here it is half past nine.”

The next day the waiting was over as an overflow crowd packed the Tremont Temple. A review published in the Boston Journal described the set: On the rear of the platform was a maroon-colored screen about 15 feet long by 7 high and a carpet of the same color spread in front, In the center of the platform stood a little crimson-colored stand, festooned with bright fringe with a tiny desk, which an open book more than covered…

A single gas lamp lit the great author as he took the stage to thunderous applause. He began with the simplest introduction imaginable: “Ladies and Gentleman, I shall have the honor and pleasure of reading you this evening some selections from my works.” A review in the Boston Journal described what transpired:

To say that his audience followed him with delight hardly expresses the interest with which they hung upon every word that fell from his lips and eyed every gesture with which his prolific genius clothed every idea embodied by the wonderful characters of his ‘Christmas Carol.’ The dolorous, surly tones of Old Scrooge, his grim humor in the interview with the first ghost, the chattering Crachits, poor little Tiny Tim, the dance in old Fezziwig’s warehouse, Scrooge’s purchase of the prize turkey , and other characters and incidents were delineated in a manner that only the author of those inimitable creations could achieve…

…it is no exaggeration to say afforded unmixed delight to all who heard it.

Following the conclusion of ‘Carol”, Dickens was compelled to break two longstanding rules he observed for his readings: firstly, the applause that followed was so deafening that Dickens was forced to return to the stage for a bow; secondly, though Dickens strictly forbad dressing room visitors other than his manager and his personal dresser, he shared a triumphant champagne toast with his friend Fields before returning to the stage to perform the ‘Trial from Pickwick’.

Afterwards the Fields and a few other friends dined with Dickens at the Parker House and all agreed that “Never before in Boston had anything called forth such enthusiasm as that night’s reading.” From his study at the former Cragie House, Longfellow recorded the event in his diary:

Dickens’s first reading and a triumph for Dickens. It is not reading exactly, but acting, and wonderful in its way. He gave ‘The Christmas Carol” and ‘Trial from Pickwick.’ We all went- a pleasant moonlight drive. I never saw anything better.

The subsequent readings by Dickens were no less triumphant. Annie Fields invited Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, Nathniel Hawthorne’s widow, to attend the following evening and she made the trip from Concord with children Julian and Rose. Dickens added a second Christmas themed piece, ‘the Boots at the Holly Tree Inn’. Annie Fields was so taken with the “cheerful Christmas story about warm relationships that cross class divisions” that she would later found a non profit venture providing inexpensive meals for the working class at establishments called “Holly Tree Inns”.

The Boston Post noted that the readings drew “thousands to the Tremont Temple” and that for the four readings alone Dickens had taken in $20,000- the equivalent of nearly half a million dollars in 2023.

Dickens subsequently departed for New York for four more readings but returned to Boston just before Christmas. Annie Fields again arranged a festive reception for Dickens, which he described in a letter to his sister in law:

When we got here, we found that Mrs. Fields had not only garnished the rooms with flowers, but also with holly (with real red berries) and festoons of moss dependent from the looking glasses and the picture frames. She is one of the dearest little women in the world. The homely Christmas look of the place quite affected us.

Annie’s husband James is credited for the genius scheduling of a return performance by Dickens, once again at Tremont Temple on Christmas Eve, thus allowing to Bostonians the priceless opportunity of seeing Dickens’ performance of ‘Christmas Carol’ on Christmas Eve. The audience was packed, shattering the attendance record of both the Tremont Temple and for Dickens himself- he had never performed in front of so many, commenting afterward “The Bostonians were quite astounding in their demonstrations. I never saw anything like them on Christmas Eve.”

He took in $3500 for that single reading, but this is nothing compared to the imprint it left upon those who viewed it. The Boston Post wrote: “The best impression….and the one that will be most permanent was made by the Christmas Carol…the audience were at times in one complete roar of laughter which Dickens could hardly refrain from joining.”

Dickens had reported Boston critically in his ‘Notes on America’, written during his first visit to America on 1842, perhaps because that tone sold better to an English audience. But on this trip, perhaps encouraged by his rapturous reception on Christmas Eve, Dickens would return to Boston after another stint in New York, and this time stay through the spring, forgoing the Parker House this time and staying with the Fields, his dearest American Friends.

During that time he gave more readings at the Tremont Temple, staged a “walking match” with James, and indulged in his morbid curiosity by touring the infamous laboratory of former Harvard Chemistry professor John White Webster- but this last is not a story fit for yuletide and is perhaps best left for another day.

I have thought of this history over and over in the years since. I perform annually in a popular Christmas Carol performance in Salem as the Ghost of Christmas Present, and after finding out that Dickens was a performer himself, I often wonder what he’d think of my performance. The only answer I’ll ever get is from Massachusetts audience members, who continue to be charmed by Dickens all these years later.

More Blogs

- Boston Historical Tours

All Blogs Hat Tip to the LOLs The remarkable tale of Margaret Hamilton is one of the highlights of our Innovation Tour. Hamilton was Director of Software Engineering for NASA’s Apollo program.

- Boston Historical Tours

All Blogs Hat Tip to the LOLs The remarkable tale of Margaret Hamilton is one of the highlights of our Innovation Tour. Hamilton was Director of Software Engineering for NASA’s Apollo program.

- Boston Historical Tours

All Blogs Dickens and a Christmas Carol Come to Boston A long time ago, longer than I would care to admit, I was asked to develop a Christmas themed tour for a

- Daniel Berger-Jones

All Blogs Anne (Marbury) Hutchinson Anne Hutchinson, puritan, wife, mother, midwife and top notch rabble-rouser. If you’ve never heard of her, it’s not your fault, probably… Anyway, I don’t know if she